9 Reasons We Have Genuine but Limited Freedom

An essay I wrote has just been published. I argue humans and God have genuine but limited freedom. The new book is What’s with Free Will? Ethics and Religion after Neuroscience, edited by James Walters and Philip Clayton.

The book responds to some neuroscientists who claim human free will is an illusion. These neuroscientists base their views on a few experiments. For many reasons, I believe they are wrong in thinking this. The experiments don’t come close to disproving human freedom.

Here is a portion of my book chapter. I offer nine reasons why we should believe humans have genuine but limited freedom:

We should affirm human freedom because…

-

belief in freedom fits the data we know best: that we are freely choosing selves. We all presuppose in our actions that we make free choices and we know this from our first-person perspectives. We have better grounds to think human freedom is genuine than think it is not.

-

it helps us make sense of other creatures, especially humans. This argument fits nicely with what philosophers call “the analogy of other minds.” I think of it often when I consider how parents raise children. Nearly all parents believe their kids have some degree of freedom, at least sometimes, and they reward or discipline their children accordingly.

-

belief in freedom seems necessary to affirm human moral responsibility. This is an obvious reason why we should believe humans are free. Without freedom, humans seem neither praiseworthy nor blameworthy. Moral responsibility requires free response-ability.

-

it’s a component of love. When it comes to humans, it’s difficult to think we can make sense of love if we think humans are not free in any sense. Robots may do good things, but unless we define love in an odd way, we don’t think robots can love. Love requires genuine but limited freedom.

-

belief in freedom seems necessary to affirm that we sometimes intentionally learn new information. Insofar as students choose to be educated, this choice presupposes free will. Insofar as we all seek to learn, we act freely.

-

it accounts for intentional actions to reject the old and welcome the new or reject the new and return to the old. Conservatives appeal to freedom when calling us to return to past ideas, and progressives appeal to freedom when calling us to embrace new ones. Intentional change presupposes free will.

-

belief in freedom is part of what motivates many people to choose good over evil. Those who believe their negative urges are beyond their control typically fail to resist those negative urges. And those who encounter evil are unlikely to resist it if they feel nothing can be done. After all, why try to combat antisocial behavior if we’re not free?

-

it is necessary for believing our lives matter. If all life is predetermined, it makes no sense to think our lives have meaning or that what we do ultimately matters. If all comes down to fate, we make no real contribution to what has already been decided.

-

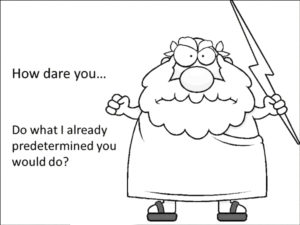

belief in freedom is most compatible with believing God loves us. This is not only true if one believes a loving God would give freedom to creatures. It’s also true for rejecting the view that God praises or punishes creatures who are not free. A fully predestining God has no grounds to judge predetermined creatures.

The final reason I list for why we should believe humans have genuine but limited freedom r efers to God. In the second half of my essay, I explore what God’s freedom might be like. But I believe descriptions of divine freedom will be inadequate if we don’t also explore the relationship between God’s love and power, creaturely freedom, and evil in the world. So I explore those ideas as well.

efers to God. In the second half of my essay, I explore what God’s freedom might be like. But I believe descriptions of divine freedom will be inadequate if we don’t also explore the relationship between God’s love and power, creaturely freedom, and evil in the world. So I explore those ideas as well.

I hope you consider getting a copy of this new book. When you read my full essay, let me know what you think of my arguments.

In the meantime, below is a short video with these 9 reasons…

Comments

This may be an expansion of #3 and 5 but it seems to me truth and rationality depend on free will. It seems the determinist wants us to believe determinism is true, but that would require we investigate the subject. Perhaps gathering enough information and assessing enough arguments to finally believe determinism is true (assuming here the trust of direct involuntary doxasticism). But the investigation presupposes freedom, otherwise why praise those who affirm the truth of determinism and chastise those who deny it? I guess all this rests on Kant’s “ought implies can” and if I ought to affirm determinism that implies I can affirm or deny its truth which seems to suggest I am free.

I like it, Curtis! Thanks!

Free will is self-evident and part of the Imago Dei/image of God. It is necessary for love, relationship, moral responsibility, cogent theodicy, etc.

A famous study about free will has been debunked. Free will: 1. Neuroscience: 0!

Thanks, Eric. If you’re talking about the Libet study, I agree. “Debunked” may be strong. But Libet’s work certainly doesn’t undermine what most people mean by free will.

Thanks for responding,

Tom

One issue I have is that reductionism pushes us towards binary thinking. As a scientist who is also a writer, poet, and general human being (!) I am often dismayed to hear people describe something at a “lower” level and then turn around to say the “higher” level somehow ceases to exist precisely because we have understood it better. For example, does Love exist? Scientists can explore love at a neurochemical level, explore the role of oxytocin, dopamine, endorphins etc. and we can learn great things about humanity at this level. But this does not mean Love now ceases to exist. And yet, many seem to think science can somehow disprove God by better understanding creation (perhaps a flaw in those who adopt a god-of-the-gaps explanation of God).

I wonder if we might be able to understand the neuroscience of free-will in a similar way, without the false dichotomy of Can We Understand It or Does It Exist?

Thanks for a great topic!

Great response, Musing Monk. I agree with your post and your final rhetorical question.

Tom

Nicely said, Tom! A lot of my friends and I are big fans of the shows “Devs,” and “Westworld,” both of which deal extensively with the questions of free will vs. determinism. This essay goes a long way towards defending the (much more intuitive, let’s face it) belief in limited but genuine free will.

Thanks for the kind words, Max!