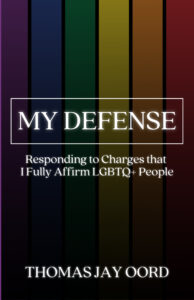

My Defense

I face a church trial in late July 2024 for being queer affirming. To prepare, I’ve written a lengthy defense. And I’ve decided to publish it before the trial to make my arguments available to the public and not just the jurors.

My arguments are published in My Defense. The eBook version can be purchased on Amazon for only .99 cents; the print version is $4.99. At those prices, I’m losing money. But I want my defense and the other trial-related documents to be affordable to just about everybody.

To start My Defense, I offer a brief history of how I changed my mind on LGBTQ+ issues. The excerpt below comes from that narrative…

I Changed My Mind

I changed my mind about “homosexuality” in 1994.

What many now call “LGBTQ+” or “queer” people and issues were in the 1990s usually subsumed under the single word “homosexuality.” Questions about gender and sexuality were emerging in unprecedented ways in popular culture at that time. Those questions were rarely discussed in the Church of the Nazarene, however, the holiness group into which I was ordained a few years earlier (1992). To my knowledge, the issues were never discussed in denominational forums, except in condemnation.[1]

In a Nazarene Theological Seminary course on religious education (taught by beloved professor Ed Robinson), two classmates and I decided to tackle “the homosexual question.” Those classmates: Dana Hicks and Reg Watson. We used the Wesleyan quadrilateral to frame our exploration, a conceptual tool that uses scripture, reason, experience, and tradition to address issues.

As I read the scholarship on the 6-8 biblical passages used to “clobber” queer people, I realized they did not apply to most queer issues in the modern world. Those who claim the Bible opposes homosexuality were also ignoring key texts about diverse sexual identities and expressions. The Bible was not as clear as I had been led to believe.

Interpreting the Bible

I began to wonder what principle I should use to interpret the Bible, particularly passages related to queer concerns. After all, almost no one thinks every Scripture verse applies today. Even those who do privilege some passages and downplay others. Few people, for instance, worry about wearing clothing of the same fabric, although there’s a passage that forbids such attire. Few people think being left-handed is wrong, but there’s a passage condemning it.

Furthermore, some practices considered essential earlier in history came to be thought nonessential. Take circumcision, for instance. Numerous biblical passages support circumcision as a nonnegotiable for God’s people. But the church eventually decided it was not required for Christians. And several biblical passages reject women leadership in the church. But a growing number of Christians, especially in the Church of the Nazarene, think those biblical passages do not apply today. Other passages reflected the patriarchal assumptions of the authors, assumptions we rightly reject today.

A question arose: What interpretive principle—“hermeneutic”—should I use to make sense of the Bible?

Love

The Wesleyan theological tradition provided an interpretive principle, and I used it then and still use it now: love. When interpreting the many voices of scripture, love should be my guide. More specifically, love ought to be the lens through which I thought about sexual matters. Love is central to Jesus’ life and teachings, and I think it’s the major theme of the Bible.

I had an idea of what “love” meant, but it took a few years to come to a robust definition. I came to believe that to love is to act intentionally, in relational response to God and others, to promote overall well-being. To love like Jesus, we should seek the flourishing of all, especially the marginalized, poor, and vulnerable. Love does good.

Hicks, Watson, and I wrote a massive paper for Robinson’s seminary class back in 1994. We argued that the Bible, as a whole, is not opposed to loving same-sex intimacy. “Homosexuality” can be healthy, we said. The experiences of many queer people points to positive elements in queer identity, orientation, and behavior. The only strong element in the quadrilateral against queer issues and people was the Christian tradition. But we found research that even questioned whether the tradition consistently opposed same-sex attraction and behavior.

Having realized I should be what we today call “affirming,” I faced another question: Could I stay in the Church of the Nazarene?

(For the remainder, get a copy of My Defense.)

[1]. One important exception was Kenneth Grider, a professor formerly at Nazarene Theological Seminary. For a helpful summary of Grider’s views, see Michael Lodahl’s essay on him in Why the Church of the Nazarene Should be Fully LGBTQ+ Affirming (Grasmere, Id.: SacraSage, 2023). Link to book.

Comments