The “Almighty” Problem in Scripture

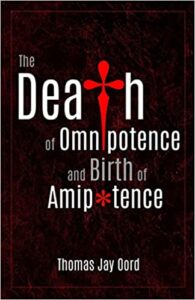

In my book The Death of Omnipotence and Birth of Amipotence, I explain how omnipotence and almighty are not rightly associated with scripture. In this essay, I lay out the problem with English translations of the New Testament that call God “almighty.”

Almighty Is Rare

“Almighty” appears ten times as a translation of Pantokrator in English versions of the New Testament. Nine of those instances occur in the Book of Revelation. We find one in Paul’s letter to the Church in Corinth.

Let me restate that Pantokrator appears just ten times in the New Testament. This scarcity is remarkable, given that many Christians think God is omnipotent, and major creeds describe God as “almighty.”

The New Testament contains about 138,000 Greek words, depending on differences among early manuscripts. This means Pantokrator occurs 0.00726% of the time. That qualifies as rare! To put it another way, New Testament writers rarely refer to God as Pantokrator, a word often translated “almighty” in English and mistranslated from Hebrew.

Pantokrator in the Septuagint

Pantokrator is a word found in the Greek Septuagint translation of the Hebrew scriptures. As I’ve shown elsewhere, it is a mistranslation of the Hebrew words Shaddai, which means “breast” or “mountains,” and Sabaoth, which means “hosts” or “armies.” These words do not mean omnipotent, almighty, sovereign, or all-powerful. In their translating work, in other words, Septuagint writers mangled the meaning of the Hebrew.

The prefix panto means “all;” the root krater or krateo has various meanings, including “hold,” “seize,” or “attain.” For instance, God holds (krateo) the stars in divine hands, according to John’s Revelation in the New Testament (1:16). Pantokrator might best be translated “all-holding” or “all-sustaining.”[1]

In her explanation of how Pantokrator emerged, biblical scholar Judith Krawelitzki says, “There is strong evidence that the [verb of] Pantokrator has been created and established by the translators of the Septuagint.” She continues, “It seems [translators] coined a new word to avoid conceptualizing Yahweh’s power with an already known word utilized to express the power of other deities, especially Zeus’s power in Greek philosophy.”[2]

Septuagint translators, says Krawelitzki, did not want to portray Israel’s God as omnipotent. “It cannot be accidental that even in the Septuagint Psalter God’s power is not conceptualized by the notion of omnipotence,” she says. “The reluctance to name God ‘the Almighty’ seems to be rooted in the texts themselves, which prescind from any kind of theoretical reflection about the extent of God’s power.”[3]

An all-holding God is not all-controlling.

Paul’s Sole Use of Pantokrator

Outside Revelation, the only reference to Pantokrator occurs in Paul’s second letter to the church in Corinth. Paul writes, “As God has said: ‘I will live with them and walk among them, and I will be their God, and they will be my people.’ Therefore, ‘Come out from them and be separate,’ says the Lord. ‘Touch no unclean thing, and I will receive you.’ And ‘I will be a Father to you, and you will be my sons and daughters, says the Lord Almighty [pantokrator]’” (2 Cor. 6:16b-18).

In this passage, Paul is quoting Septuagint translations of 2 Samuel 7:8, 14.[4] These verses draw from the Hebrew, Yahweh Sabaoth. We earlier saw that this phrase is rightly translated as “Lord of hosts” or something similar, not “the Lord Almighty.”[5]

The only time the Apostle Paul—who wrote more New Testament books than anyone—refers to Pantokrator is when he cites the Septuagint.[6]

Pantokrator in Revelation

In Revelation, Pantokrator occurs nine times. English Bibles often render the word “almighty,” as in the phrase “the Lord Almighty.” In most instances, Pantokrator is a phrase of worship, with little context to discern what it means (see 1:8, 4:8, 11:17. 15:3, 16:7. 19:6, 21:22).[7] In these cases, Pantokrator serves a liturgical function without identifying the precise connotation of the word.

John twice uses Pantokrator to compare God to creaturely kings and emperors (16:14, 19:15). His point seems to be that God is or will be more powerful than earthly leaders. In these cases, notes Eugene Boring, “‘almighty’ is bound to the title ‘Lord’ (kurios), a title which properly belongs only to God but has been usurped by the emperors and used of Domitian and the other Caesars in the emperor cult.”[8]

While Alexander the Great and other Hellenistic and Roman rulers claim to exert universal power, only God’s influence is truly universal.[9] John’s point is not that God controls, can do absolutely anything, or has all power.

His point is that only a universal leader—God—exercises universal influence.

Krateo and Dunamis

We earlier saw that Pantokrator is a compound word, with the prefix meaning “all.” In the New Testament, the verb form of the word—which refers to active power—is translated as “hold,” “seize,” “cling,” “attain,” or something similar. In other words, the verb form of krat does not mean controlling, doing absolutely anything, or having all power.[10]

Dunamis is the Greek word in the New Testament translated as “power.” It occurs ten times as often as Pantokrator and means “ability,” “strength,” or “influence.” Biblical writers use dunamis to refer to the power expressed by God, Jesus, and creatures. The verb form of the word—dunamai—occurs about 20 times more than Pantokrator in the New Testament. It also refers to the ability to do something.

Neither the verb nor the noun forms of dunamis have a prefix meaning “all” in the New Testament. If terms like pantodunamis or pandunamai were present in the Bible, we would have scriptural words that straightforwardly mean “all-powerful,” “almighty,” or “omnipotent.” Such words are not present in scripture.

Never.

No New Testament passages record Jesus calling God “almighty.” Nor does he call God “omnipotent.” Jesus doesn’t use Pantokrator or some version of dunamis to describe God as all-powerful. He says God is greater than himself (John 14:28), and he praises God in various ways. The word Jesus uses most often for God is “Father” or abba, a term of loving endearment, not overriding control.

Conclusion

While New Testament writers describe God as having immense power, they do not use words that mean “omnipotent,” “almighty,” or “all-powerful.” They do not use words that mean God has all power, is able to do absolutely anything, or controls. If we think Jesus knows God best, his not calling God omnipotent should influence how think about divine power.

Omnipotence isn’t in the New Testament, and “almighty” rests on a mistranslation.

Notes

[1]. Ian Robert Richardson notes that “when considering God’s power as providentially sustaining the universe, kratein was followed by the accusative case because that was used to express ‘holding’ rather than ‘reigning.’” See Richardson, “Meister Eckhart’s Parisian Question of ‘Whether the omnipotence of God should be considered as potentia ordinata or potentia absoluta?’” Doctoral Dissertation (King’s College London, 2002), 17. The 2nd-century bishop Theophilus, for instance, says God “is called Pantokrator because He Himself holds (kratei) and embraces (emperiechei) all things (ta panta).” Ad Autolycum 1, 4.

[2]. Judith Krawelitzki, “God the Almighty? Observations in the Psalms,” Vetus Testamentum, 442-43. Krawelitzki says that “according to the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, less than 1% of the approximately 1400 references for [verb form of] pantokrator can be found in pagan literature” (cf. G. Kruse, “Pantokrateo” PW 18,3 (1949), 829-830). Although the adjective form of pantokrator is found only in 2 Mac. 3:22, it can be found often in Greek literature (cf. O. Montevecchi, “Pantokrator,” in Studi in onore di Aristide Calderini e Roberto Paribeni II [Milano, 1957], 402). On the use of pantokrator in Greek philosophy, see H. Hommel, “Pantokrator,” Sebasmata (Tübingen, 1983), 142-143; R. Feldmeier, Nicht Übermacht noch Impotenz. Zum biblischen Ursprung des Allmachtsbekenntnisses, eds., Der Allmächtige. Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Gottesprädikat (Göttingen, 1997), 25, 30-31; M. Bachmann, Göttliche Aumacht und theologische Vorsicht Zu Rezeption, Funktion und Konnotation des biblisch-frühchristlichen Gottesepithetons pantokrator (SBS 188; Stuttgart, 2002), 147-160.

[3]. Krawelitzki, “God the Almighty,” 443.

[4]. A minority of scholars believe Paul is quoting Jeremiah 31:35 here. Yahweh Sabaoth is also used in Jeremiah, so my point stands in either case.

[5]. The New International Version is unique among translations when it uses “almighty” to render two New Testament words. In Romans 9:29 (Paul is citing Isaiah 1:9) and James 5:4, the NIV translates “hosts” in Greek as “almighty.” These are additional mistranslations of Sabaoth.

[6]. In his analysis of Paul’s reference to Pantokrator, Wilhelm Michaelis says “it has only a loose connection with the dogmatic concept of the divine omnipotence, which is usually linked with the omnicausality of God” (Michaelis, παντοκράτωρ, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, 914-15). Paul seems to switch back and forth between the Hebrew and Septuagint when citing Old Testament texts. He seems to be citing 2 Sam 7:14 here, and this passage does not include the words “says the Lord Almighty.” None of the Old Testament texts Paul quotes say, “Lord Almighty.” But it also possible Paul has 2 Sam 7:8 when he writes, “says the Lord Almighty,” where Nathan says, “thus says Yahweh Sabaoth.” I thank Bill Yarchin for alerting me to this.

[7]. Michaelis notes Pantokrator is a title found in early Jewish prayers and its liturgical use influenced the writer of Revelation (Ibid.).

[8]. M Eugene Boring, “The Theology of Revelation: ‘The Lord God the Almighty Reigns,’” Interpretation, 259.

[9]. See also “Almighty,” The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, A-C, Vol. 1 (Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon, 2006), 105.

[10]. For instance, see verb forms of krateo in Matthew 9:25; 12:11; 18:28; 21:46; 22:6; 26:4; 26:48; 26:50; 26:55; 26:57; 28:9; Mark 1:31; 3:21; 5:41; 6:17; 7:3; 7:4; 7:8; 9:10; 9:27; 12:12; 14:1; 14:44; 14:46; 14:49; 14:5; Luke 8:54; Acts 2:24; 3:11; Colossians 2:19; 2 Thessalonians 2:15; Hebrews 4:14; 6:18; Revelation 2:1; 2:13; 2:14; 2:15; 2:25; 3:11; 7:1; 20:2.

Comments